Rust never sleeps and neither does John Einarson.

Check out Einarson’s archives including videos, liner notes, and articles on some of the industries most well-known artists.

Videos

Anthony Peake interviews musician, journalist and author John Einarson.

John Einarson wrote the Juno-nominated Bravo TV documentary “Buffy Sainte-Marie: A Multi-Media Life”, 2016.

Watch an interview with Richie Furay, co-author with John Einarson, of There's Something Happening Here: The Story of Buffalo Springfield: For What It's Worth.

Articles

John Einarson has published hundreds of magazine and newspaper articles worldwide. Here are some sample articles from the ‘Winnipeg Free Press’, ‘Boomer Magazine’ and ‘Lifestyles 55’.

-

Do You Believe In Magic? Zal Yanovsky Helped Make It

Winnipeg Free Press

Article by John EinarsonZalman Yanovsky died last Friday at his home in Kingston, Ontario of an apparent heart attack. The wire services carried the story across the country: sixties-era guitarist turned chic restauranteur dead at 58. For most editors the report scarcely warranted more than a paragraph or two. Old news; another boomer-era idol gone.

In the annals of pop music history, Zal Yanovsky’s name is not likely to elicit more than a passing reference, if that. He was, for those unacquainted with that odd, ethnic-sounding moniker (and that’s probably most of you), the lead guitarist in the Lovin’ Spoonful, a mid-sixties New York folk-rock group that enjoyed a handful of hits that remain staples of oldies radio today: Do You Believe In Magic, Daydream, You Didn’t Have To Be So Nice, Summer In The City. He wasn’t the lead singer, not even the principal songwriter, but if you ever saw the Spoonful, even a photograph of them, you knew instinctively that Zal, with that impish twinkle, was the heart and soul of the group.

Back in 1965, my hero, bar none, was Zal Yanovsky. Why? Sure, he was an innovative guitarist capable of clever country-flavoured licks and riffs, but it was more than that. Much more. You see, Zal Yanovsky was a Canadian.

In the endless parade of long-haired Beatle-booted wannabes ascending or descending the pop charts on any given week in the mid sixties, most were either of British origin, Liverpudlian preferably, or American. There was the odd foreign interloper: Manfred Mann was from South Africa (that explained the Amish-like beard); Los Bravos was an odd mix of Germans and Spaniards; Them, featuring a diminutive, fiery maned Van Morrison, had escaped from Northern Ireland; the Easybeats hailed from the land down under. But how many Canadians could you possibly spot on a Sunday evening broadcast of the Ed Sullivan show? Robert Goulet? Paul Anka? Wayne and Shuster? Gisele Mackenzie? Hardly the hairy, bell-bottomed variety.

I loved the Spoonful’s music from the get-go. Do You Believe in Magic was an infectious affirmation of the sheer joy of rock ‘n’ roll and a mainstay on my Seabreeze for months before Daydream replaced it. Once I discovered via Hit Parader magazine, which my Mom faithfully bought for me each month, that the Spoonful’s lead guitarist was a Canuck like me, that was it. I had found my idol, my role model. Within days I began the campaign to wear down my parents for a guitar. Forget George Harrison or Brian Jones; I wanted to be Zal Yanovsky.

I’m sure I was no different from hundreds of other teenagers up here in the frozen wastelands who came to identify a sense of national pride in that rather shaggy looking fellow with the large nose and the odd-shaped guitar. Lord knows, finding a suitably long-haired Canadian on the pop charts in ’65 was rare, indeed, and cause for waving that new flag of ours. If Zal could make it in the pop world then surely other Canadians could too, we reckoned; even someone as peculiar looking as Zal. He became, by default, Canada’s first Beatle-era rock star and the inspiration for Canadian kids to take up the guitar, drums, organ, whatever.

In the pre-CRTC Canadian Content world of the early sixties, Zal had, like so many others, fled Canada for greener pastures and paycheques in the United States. He and fellow Canuck Denny Doherty (later to find fame as the velvet-voiced tenor in the Mamas and the Papas, another point of sixties-era Canadian pride) had migrated to New York where, after a few false starts, Zal hooked up with John Sebastian to form the Lovin’ Spoonful. The group was, for a brief moment in time, considered rivals to the Beatles and rode the toppermost of the poppermost. I can vividly recall the Spoonful on the Sullivan show, Zally, the clown prince of rock ‘n’ roll with a rubber frog dangling from the neck of his guitar, mugging to the audience and muscling in on Sebastian whenever the camera swung his way. What a guy! What a Canadian!

The Star Weekly ran a cover story on our favourite Canadian pop star in early 1967 featuring recollections from family and friends including journalist Larry Zolf who recounted the time Zal lived in a downtown Toronto laundromat, or how he had driven a tractor through a building on an Israeli kibbutz. But by the time the story ran, Zal was out of the Spoonful under a cloud of marijuana smoke following a bust in San Francisco. In exchange for not being deported, Zal named the dealer and in so doing incurred the wrath of the burgeoning counterculture.

The next time I heard Zal’s name was two decades later in association with a trendy noshery in Kingston dubbed Chez Piggy. The name was pure Zally, the madcap guitarist now an entrepreneur. My publisher, who resided in Kingston, took me to dinner at the popular eatery and promised to introduce me to my hero but, alas, he was off that night. I had brought my dog-eared copy of the Star Weekly all the way from Winnipeg for Zal to autograph.

A few years later, in 1996, I was invited by Steppenwolf’s John Kay to be his guest at the Juno Awards banquet held to honour Kay, Denny Doherty, David Clayton-Thomas, Domenic Troiano, and Zal Yanovsky as inductees into the Canadian music Hall of Fame. It was a star-studded evening boasting Canada’s rock royalty. I mingled with the likes of Robbie Robertson, Ronnie Hawkins, Buffy Ste. Marie, and Shania Twain. As Kay’s biographer I was thrilled to accompany him, but I had ulterior motives. I asked Kay to introduce me to Zal and he graciously agreed. I was beside myself with anticipation all evening. I had once again packed my Star Weekly in hopes of an autograph but, at the last minute, left it behind at the hotel fearing embarrassing either Zal (hardly) or myself (definitely).

Later in the evening as my wife and I sat at a front table with the Kay’s, Zal and John Sebastian ambled over. Zal looked much like he had in the sixties, same long stringy hair, ample nose and mischievous grin, though a little paunchier around the middle, like an aging elf. Kay introduced me. Turning crimson, I stuck out my hand and stammered, “Pleased to meet you.” “Yeah, thanks,” he smiled, shaking my hand vigourously before moving on to the next table. All I could think of was that Star Weekly magazine.

A few months later I worked up the courage to call Zally at Chez Piggy to pitch him on the idea of a biography. After all, he was a Canadian legend worthy of deification. “Not interested,” was his polite but firm reply. I learned from my publisher that Zal loathed dwelling on his illustrious past and did not suffer lightly those who attempted to do so.

I still have that Star Weekly. Maybe someday I’ll do that biography. But it won’t be the same without Zal.

-

Led Zeppelin

Winnipeg Free Press

Article by John EinarsonYou might not know it to look at me – middle aged, hair receding, waistline expanding, glasses – but I’m cool. What gives me my cool quotient, you ask? Well, let me put you wise: I opened for Led Zeppelin. That’s right, I’m the school teacher who opened for that legendary heavy rock group (though there are a dozen or more others in town who could also rightfully lay claim to the same boast though I’m certain I’m the only teacher in the bunch). If it had been Paul Revere and The Raiders or the Lemon Pipers my currency in cool wouldn’t have survived the decade.

Given the fact that Led Zeppelin continues to sell albums by the truckload (recent Billboard stats peg their total sales in excess of 70 million and counting) and with young converts born long after the group folded rediscovering their unique brand of guitar-heavy, blues-based primal rock every day, my cool status appears fairly secure for awhile yet.

It’s a ritual played out at least once or twice a year of my teaching career. I can’t even recall how the story first circulated some twenty years ago. Someone invariably poses the question in the waning moments of an otherwise routine grade eight class on some aspect of Medieval European history. It took this year’s crop of students a little longer to summon up the courage to ask but inevitably the question came up last week. “Mr. Einarson, did you really open for Led Zeppelin?” a brave soul sheepishly inquires, testing the waters to see whether the oft told rumour is in fact true. Smugly I retort, “Do I look like someone who opened for Led Zeppelin?!” Pause while the class assess me up and down to see if I measure up to share a stage with the likes of Jimmy Page’s guitar strutting or wild-maned singer Robert Plant’s provocative gyrations.

I have several obvious strikes against me not the least of which being my thinning hair when held up to the flowing locks of Page and Plant, and my vocation as a twead-jacketed educator. “Nope,” comes the invariable conclusion with a snicker. “He’s a teacher! No way.” To which I then smile, “Well kids, in fact I did open for Led Zeppelin.” Looks of awe and a chorus of “Cool!” follow. Whispers throughout the hallways carry on for the next few days as I walk by. “He opened for Led Zeppelin!”

It matters not that my name appears in the credits of textbooks and teaching materials from grades eight through eleven, nor that I authored a half dozen rock biographies. My status in the eyes of my students is forever inexorably linked to that archetypal heavy rock group.

In what seems like another lifetime, the once and mighty Zeppelin did indeed perform in Winnipeg on August 29, 1970 during a summer of festivities marking Manitoba’s centenary. It was an eventful concert that seems to have eluded the myriad of Zep biographies and rock encyclopedias. And not just because of my presence in the story.

Billed as Man Pop 70, the rock festival to end all Winnipeg festivals was booked for the outdoor football stadium and boasted a slate of acts drawn from suggestions mailed in by local music fans. The big winner was Led Zeppelin followed closely by Iron Butterfly. At the time, Zeppelin were riding high with their second album driven by such workhorses as Whole Lotta Love and Living Loving Maid (She’s Just A Woman) and stood poised to conquer the globe later that year.

My band, Euphoria, was the first of a handful of local acts to take the stage in early afternoon under overcast skies. With in excess of 14,000 in attendance largely there to witness the headliners and not the skinny seventeen year old in the cowboy hat, we were given a polite response and sent on our way. No matter, my place in history had been secured. Or had it?

By the time Vancouver’s Chilliwack launched into their rather prophetic invocation Raino, Mother Nature took up the challenge with a light drizzle that soon turned into a torrent. The decision was quickly made to move the concert into the adjacent arena and carry on. Amps and drums were humped indoors, dried off and reassembled on a jerry-rigged stage under the watchful eye of Queen Elizabeth. A makeshift PA comprised of two piles of Garnet speaker cabinets was hastily pressed into service. In the end it would prove to be one of the arena’s finest hours.

Just after the clouds opened up I managed to escape home to change out of my wet stage clothes only to return to find the arena sealed tight, full literally to the rafters. With the arena’s capacity falling slightly short of that of the stadium many ticket holders were turned away, noses pressed against the glass doors. Miraculously a riot had not ensued.

In an inspired moment I flashed my performers badge and informed the bewildered security guard on the other side of the glass that I was due to perform inside. To him, I was just another longhaired musician so the door quickly swung open wide enough for me to squeeze through leaving several hundred unfortunate souls outside in the rain.

Inside, a visible cloud mix of condensation, perspiration and funny smelling cigarettes hovered low overhead as the crowd dried off and rejoiced in their good fortune. The Youngbloods’ Get Together, a paean to the Woodstock generation’s peace and love credo, went down well while newcomers the Ides Of March rocked out with I’m Your Vehicle Baby. The indomitable Iron Butterfly, hardly known for musical finesse but ever willing to oblige, gave us In A Gadda Da Vida ad nauseum replete with obligatory twenty minute drum solo.

Meanwhile rumours spread through the throng like a brush fire. Would Zeppelin show? Comfortably ensconced at the International Inn, the quartet was high and dry (literally, one suspects) with a contract rider stipulating that in the event of rain, they did not have to perform. Their fee, however, was still due in full, some $50,000. Nice work if you can get it.

Local chanteuse Dianne Heatherington, never one to pull her punches, somehow managed to bully her way into their room and shame the party-hearty Zep boys into doing the right thing and giving the huddled mass what they had endured so much and waited so long to hear.

So, well past midnight and under less than ideal circumstances, Page, Plant, Bonham and Jones mounted the stage to delight the weary but welcoming assemblage with a spirited set. Whether any of the surviving band members care to remember that performance or not, some 10,000 ecstatic fans will never forget the night the indefatigable Zeppelin shook a rain-soaked Winnipeg audience with the show they didn’t have to play. As for me, it had been a long day and by about two in the morning with Plant still prancing and Page wringing out blues licks from his cherry red Les Paul slung low on his waist, I quietly slipped out a side door to head for the comfort of my bed.

Though Mssrs. Plant, Page and I never crossed paths that night nor exchanged a single word between us, we share a special bond and I am forever in their debt. Their remarkable longevity in a business that relegates even last year’s hitmakers to golden oldies has bestowed upon me a legacy that has endured far longer than my hair. Much like the Doors phenomenon, Zeppelin have sold more records since breaking up as during their eleven year run.

But as long as Houses Of The Holy continues to ring up cash registers and Stairway To Heaven fills dance floors as the perennial last dance of the night, I will remain cool. I opened for Led Zeppelin.

-

Summer Flashbacks Drive-In Restaurants

The Winnipeg Free Press

Article by John EinarsonIn the sixties where could you go on a warm summer evening? The drive-in restaurant. You’d hang out with friends, have a burger, and check out the cars.

While each neighbourhood had its favourite drive-in, such as the Sals and the A&W on Pembina, or the Big Boy on Portage Avenue, two drive-ins transcended local patronage to become Winnipeg institutions: the Red Top on St. Mary’s Road in St. Vital and the Thunderbird at Jefferson and McPhillips. They were two of the most popular teen spots.

“We used to have two security guards every Friday and Saturday night directing traffic in and out,” recalls Red Top owner John Scouras. “Cars would drive in and out from seven in the evening until eleven trying to get a spot to park. It was always full.” Carhops took orders as teens ate in their cars. Hamburgers were 25 cents, fries 15 cents, soft drinks a dime, and milk shakes a quarter.

CKRC’s Jim Paulson broadcast the ‘Red Top Rendezvous’ live each evening from a trailer parked in the Red Top lot. Speakers blasted the music to the waiting cars. “Every tenth or fifteenth car that drove in they used to give them a free hamburger or a 45 record,” smiles Scouras. “We even had a Red Top song written and recorded by one of the local bands.”

While the freshly-made burgers and fries were an attraction, so was the radio connection. “Kids came to meet the bands and the radio deejays,” enthuses Glenn MacRae, of The Crescendos. “Deejays were as popular as bands in those days.” Musicians recognized the opportunity for promotion. “We would go to the Red Top every night in our van and Jim would say, ‘Here comes the Crescendos! Let’s get them over here and find out where they’re playing this weekend.’ It was an event just to go there. The place would be packed.”

A family-owned business since opening in 1961, Scouras feels drive-ins filled a need back then. “There were so many kids. They had no place to go and nothing to do. This was a new thing for them, to sit in the car and have a root beer and a hamburger. Guys met their future wives here.”

Across town, the Ginakes brothers – Jimmy, Perry and John – opened the Thunderbird in 1960. John continues to run the popular North End landmark. “We were the last business in this end of town,” he recalls, “right at the end of McPhillips. There was field all around us.”

According to Ginakes, “Kids were easier to get along with in those days, more responsible. There was an innocence.”

“It always seemed like you would see the same crowd when you went there,” notes longtime Thunderbird patron Chief Justice Benjamin Hewak. “Being raised in the North End, those are my roots. I still meet my friends there and catch up on everything.”

Both Scouras and Ginakes credit a consistent fare for their loyal base. “People continue to come here because they know they’ll get the same food they’ve always had,” stresses Ginakes. “We don’t change things around.” Today he finds himself serving the grandchildren of former Thunderbird regulars. “There are families who have been coming here, third and fourth generation now, since the day we opened. Burton Cummings still comes here.”

That personal connection differentiates establishments like the Red Top and Thunderbird from other fast food franchises, suggests Ginakes. “We have the type of clientele who like a one-to-one relationship where you know them by their first name. They feel at home. The fast food business today is impersonal, they’re just there to take your order.”

The seventies brought change to the drive-ins. “When the drinking age lowered to eighteen, drive-in restaurants lost 40% of their business,” notes Scouras. “We were forced to drop the carhops.”

He sees the family-owned drive-in as a dying breed. “When we first opened there were only ten restaurants from the Norwood Bridge to Dakota Crossing. Now there are a hundred. The American franchises are taking over.”

-

Whatever Happened to Oscar Brand

Winnipeg Free Press

Article by John EinarsonHere’s a trivia question. The Sesame Street character Oscar the Grouch is named for what Winnipegger? The answer: folk music legend, sing/songwriter and broadcaster Oscar Brand.

“I was on the original board of the Children’s Television Workshop,” he explains from his home in New York, “and I was so fastidious about everything that I gave people a hard time. So they named the grumpy character after me.”

In an illustrious career that spans over 65 years, Oscar Brand is one of the most celebrated entertainers in the world. He has written for Broadway and film, recorded some 90 albums, hosted television shows in both Canada and the United States, and hosted a radio show on New York’s WNYC every week since 1945. He also penned one of Canada’s greatest folk music anthems, Something to Sing About (This Land Of Ours). “I was in a unique position,” he recalls, “because I had one foot in Canada and one foot in the States. I would do well in both but it was the doing well in Canada that I liked the best.”

Oscar was born in 1920 to a Jewish family in Winnipeg’s ethnically diverse North End. “I grew up on Lusted Avenue with a big open field at the end of it back then. It was an exciting time. I can remember horses on the street and my brother tickling their hooves and trying to ride them as they galloped away. Lusted, to me, was a perfect picture of Canada.” His father, an early settler in the Portage la Prairie area, was a linguist employed by the CPR to greet newly-arrived immigrants. “He knew all the languages. At age 14 he started as a translator for the Indians. He’d learn their languages. The Hudson’s Bay Company hired him. He led an interesting life.” Oscar’s extended family was equally colourful. “One of my relatives was an ice carrier, another was a smuggler.”

At age eleven, Oscar moved with his family to New York. “We never wanted to leave. We loved Winnipeg and Manitoba.” He graduated from Brooklyn University with a degree in psychology (“I couldn’t get into a college in Canada”) and served in the US army during World War II. Following the war, he joined WNYC presenting Oscar Brand’s Folksong Festival, the longest-running show in radio history and winner of two Peabody Awards. He also began writing, both music and books, as well as recording. One of his songs, A Guy Is A Guy, became a hit for Doris Day in 1952. “The original iteration of that song I think I learned in Montreal. It was really about the British soldiers. It became number one around the world.” Oscar’s songs have been recorded by Ella Fitzgerald, Harry Belafonte and the Smothers Brothers. In addition, he wrote commercials for Maxwell House coffee and Oldsmobile among others.

Oscar composed the music for two Broadway musicals, A Joyful Noise starring John Raitt and The Education of Hyman Kaplan featuring Hal Linden and Tom Bosley. “I wanted to write a show on Broadway. That was my goal.” In 1963 he returned to Canada to host CTV’s Let’s Sing Out which featured many of this country’s finest folk performers as well as newcomers such as Joni Mitchell (filmed at the University of Manitoba in early 1964). Over the years he has appeared alongside the likes of Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, Ian & Sylvia, Woody Guthrie, the Kingston Trio and Pete Seeger.

“I did a lot of Canadian television and radio. I loved the popular music of Canada. I was brought up on it. Unfortunately many of my songs were blacklisted in the States for being too political. Canadians were a little more tolerant. But the reality was that you had to go to the States where the business was happening. However, I always made sure there were Canadians on my programs.”

In 1987 Oscar was awarded an honorary doctorate from the University of Winnipeg and returned once again to his hometown last year to appear at the 37th annual Winnipeg Folk Festival where he received the Order of the Buffalo Hunt from the province. “I’m at an age now where they bestow honours and awards on me,” jokes the spry 91 year old. He holds honorary degrees from several American universities. Oscar is currently writing his autobiography. “It’s been one hell of a ride. That’s what I’m titling the book.”

Despite becoming a naturalized American, Oscar still calls Winnipeg home. “It was always Winnipeg for me. I always came back even when people were fleeing Winnipeg. I bounced back and forth between Canada and the States but I always thought of Winnipeg as my home.”

-

Do you remember Teen Dance Party?

Boomer Magazine

Article by John EinarsonIt was a dubious formula for television success: a group of teenagers in a large unadorned studio dancing to records. Yet success it was. Between 1961 and 1968, CJAY TV’s Teen Dance Party was, to borrow from current promotional clichés, must-see TV for Winnipeg teens. Every Saturday at noon teens across the city tuned into the one hour show to hear the latest hit records, see the current cool fashions, and learn the hippest new dance steps from the Pepsi Pack. And for those with enough confidence in their footwork, you might get the opportunity to dance on the show and maybe become a local celebrity.

“It was just a bunch of kids having fun, dancing and enjoying the music,” remembers Sharon Benjaminson (nee Sopko) fondly. She and her sister Darlene became Teen Dance Party regulars. “The camera men would move around you as you were dancing and suddenly the light would go on and you’d realize you were on the air so you’d try not to be nervous. Kids would recognize you no matter where you went. It was kind of like being a celebrity because you might be on an escalator in Eaton’s and you’d see kids looking at you. I’d be thinking, ‘I just go and dance on a TV show. I’m no one special.’”

Original Pepsi Pack member Marta Jack (nee Rehberg) still gets recognized for her seven year stint on the show. “All my life it’s followed me wherever I am. For example, I was at the New York Art Gallery a few years ago. You’re in New York so you don’t expect to be recognized or to see anyone you know. I walked into the gallery and someone came up to me and said, ‘Oh my god, you were on Teen Dance Party in the Pepsi Pack!’ I couldn’t believe it. I went through customs on the way back with my friend. She had her luggage all torn apart but the customs official looked at me and said, ‘Weren’t you on Teen Dance Party?’ So he just waved me on through. That show has definitely been a big part of my life.”

The concept for the show was hardly original. American Bandstand had debuted in Philadelphia in 1952 and from 1956 onward was hosted by Dick Clark. Dozens of local television stations across North America had their own version of the show by the time fledgling CJAY TV premiered Teen Dance Party in the fall of 1961. Hosted by CKY radio deejay Peter Jackson (PJ the DJ), neatly-attired teenagers between the ages of 14 and 18 jived or twisted to 45s spun while television cameras wove through the dancing throng. Sponsored by Pepsi Cola, the show presented a clean cut image of teens. No Blackboard Jungle leather-jacketed riff raff; guys wore sports coats and slacks, girls decked out smart dresses.

A review of the premiere show in The Winnipeg Tribune noted “The kids at the station looked as though they were really enjoying themselves. Host Peter Jackson, better known as PJ, did a wonderful job for someone who said he was nervous – acting casual and natural throughout the whole program.” Local band The Chord U Roys performed on the inaugural show and also backed Portage la Prairie shoe salesman-turned-singer Gary Cooper (who also recorded as Gary Andrews). There was no denying the drawing power of the show. “We were all still high school kids,” recalls Chord U Roys guitarist Terry Kenny, “and we ended up with two years of bookings from that one appearance.”

By 1963 Jackson was out as host. Rumour had it that a casual on-air reference to Pepsi making a good mix offended the sponsor’s teen-oriented sensibilities and the station’s squeaky-clean image for the show. His replacement would come to define Teen Dance Party in the memories of Winnipeg teens. Winnipegger Bob Burns had begun his broadcasting career in radio, first Timmins, Ontario and Thunder Bay before taking a staff announcer position at the newly-opened CJAY TV. The self-described oldest teenager, Burns was 29 when he assumed the hosting job. Despite his age, he proved to be adept at relating to the younger generation. As Marta Jack recalls, “PJ the DJ wasn’t as much of a presence on the show as Bob. Bob used to get right into the crowd and approach you and ask you questions. He walked up to me on his first show and asked me, ‘How old do you think I am?’ and I replied ‘45?’. To me he was just this older guy in charge of the show. He got a kick out of that and said to me, ‘I think I’m going to like you.’”

Burns chose Jack, Sandra Zagezewski and Alana Geller to be the Pepsi Pack. “Bob had a knack for picking people for specific things,” Jack points out. “But you were expected to come up to his expectations.” Along with three boys, the group would learn the latest dance crazes and demonstrate them on the show.” The exposure made the girls role models. “We often went out to community clubs with Bob if he was hosting a dance and we would be a featured part of the evening. The community clubs were really jumping back then. After our routines we would mingle with the kids and talk.”

Another Teen Dance Party regular was Jack Skelly whose rough exterior belied a mischievous heart of gold. Sharon Benjaminson was Skelly’s dance party on the show. “We met at Teen Dance Party and we became close friends but we weren’t dating or anything,” she explains, adding, “Bob Burns did a lot to help Jack because Jack was on the road to a lot of problems. He had a reputation for being a tough guy before he started coming on the show.”

“Bob could pick out a trouble maker,” notes Marta Jack, “and if you were then you didn’t get in. And if you didn’t treat the girls properly you weren’t allowed back. I remember there were a few of these big tough North End guys that Skelly knew and they came to the studio one Saturday to be on the show. Bob just walked right over to them and said, ‘We have a choice here. You can come in and dance with some really beautiful girls and enjoy yourselves or you can cause a problem and you will never be allowed in again. Which is it?’ Skelly’s face broke into a big smile and he replied, ‘I want to dance with the girls.’ Bob had zero tolerance. There was a huge respect level that he encouraged. There was never a problem for the girls. Bob really turned a few lives around, especially Jack Skelly’s.” At the conclusion of each and every Teen Dance Party, Burns would intone, “Be good because it’s smart to be good!”

The girls certainly were beautiful. “My friends and I, we watched it for the chicks,” laughs Michael Gillespie. Indeed, everyone had their favourites. “There were a couple of girls who turned my heart a-flutter.” Gillespie, however, saw something more than pretty girls in Teen Dance Party. “It was more pertinent to our lives here than Dick Clark and American Bandstand which had nothing to do with my world. Teen Dance Party represented us, Winnipeg teens. The kids on the show were wearing the same clothes that we wore, Monarch Wear Tee*Kays and all that. We could relate to the show and participate in it. It was ours.” Adds Joey Gregorash, “Everybody watched it whether they admitted it or not. Most guys watched it because there were chicks on the show or to learn the new dances to try out later that night at the community clubs.”

Initially the show drew teens mostly from the North and West Ends, the latter due to its proximity to Polo Park. “I’d say it was about 50/50,” says Marta Jack. However, in later years kids from across the city appeared on the show. Interesting to note that the crowd was almost exclusively white, reflecting the years before the city’s current multi-racial character. Fred James was the lone black regular for several years claims Sharon Benjaminson.

Each Saturday morning teens began lining up at CJAY’s Polo Park building. The doors opened at 11:30 and they filed into the studio. “They did expect us to dress nicely,” confirms Marta Jack. “If you showed up as a slob you wouldn’t get on. We were all very conscious of our clothes and liked to dress up. Bob would always come around and tell us we looked lovely in a very formal and gentlemanly manner. And he’d ask the boys if they had complimented their dates on how they looked. He really believed in the niceties and instilled that in a lot of boys. Believe me, Skelly learned a lot.”

Besides dancing with the regulars, Skelly was often featured miming to “The Surfin’ Bird” or “My Boy Lollipop”. Sandra Zagezewski’s big mime number was “These Boots Are Made For Walking”.

The live one-hour show would begin at noon. Following a short break at 1:00 to freshen up and grab a bite, taping for the two Bob and the Hits segments would commence. By the mid sixties, Bob and the Hits took the Teen Dance Party concept to weekdays appearing in two half-hour shows Tuesday and Thursday at 5:00 pm.

Being a regular on the show fostered a sense of community both on and off camera. “We would meet as a group and go to the community club dances together,” recalls Sharon Benjaminson. “Skelly was like the president of our group. He would decide where we would go.” Adds Marta Jack, “We always used to go out as a group so the chances of us getting hit on were nil. If anyone even looked at us the wrong way Skelly would give them the look and they’d go away.” To Burns, the regulars were like family. “We were welcomed in his home and invited over for barbecues and things. We were like his other children. He spent a lot of time with us.”

One unlikely visitor to CJAY’s television studio was Neil Young. Kelvin High School twins Jacolyne and Marilyne Nentwig became regulars on the show. Neil dated Jacolyne and remembers accompanying her to the show. He did not, however, join in the dancing, choosing instead to watch from beyond camera range. A photograph of Teen Dance Party reveals Young, in tweed sports coat and short hair, standing against a wall with two other boys while teens dance.

Burns’ prominence among the teen community led to a major role in the local music scene as both manager and record producer. He produced several early Guess Who recordings including “Shakin’ All Over” and managed the group for a time. He also produced the Sugar & Spice hit “The Cruel War”. “Bob was a real connoisseur of music,” states Marta Jack. “His first love was the music. He taught us what to listen for and opened our eyes to the musicality, not just the beat.”

Local bands would appear on Teen Dance Party promoting their records. “We would go on and mime our latest records,” remembers Mongrels singer Joey Gregorash. “We mimed to ‘Funny Day’ and had to add a little dance move. It was cheesy but all the other bands were doing little moves. It was fantastic exposure for the bands. Bob really supported the local music scene and gave a lot of people here a good start in this business.”

On January 27, 1968, Sugar & Spice made their public debut on Teen Dance Party. “It was absolutely critical to our whole strategy in launching the group,” notes manager Michael Gillespie. “Getting the band on television was key to all that before they ever performed live. Having Bob Burns introduce the band to the public, we couldn’t have asked for a better start. We were euphoric at debuting on that show.” Burns became a mentor to the neophyte manager. “He was a tremendous promoter and a real confidence-booster for the band. He gave us all the advice he had and we really appreciated it all. He wasn’t afraid to share his advice and experience. The more I got to know Bob over the years the more I got to understand the depth of his involvement in the music business. He was a major player on the scene.”

In August of that same year, Teen Dance Party and Bob and the Hits were cancelled, victims of changing times and tastes. “Fewer kids wanted to dance as much,” sighs Marta Jack. “Kids were different.” The community club dances which had initially given rise the show were dying out. Burns went on to produce the teen-oriented Young As You Are the following year, hosted first by the ill-suited Gary Chalmers before being replaced by Joey Gregorash. The 5:00 pm Saturday show kick started Gregorash’s long career in television and radio. “I will forever be grateful for what he saw in me as a host,” he affirms. “He had faith in me and trusted me and my abilities to MC a show.” Young As You Are focused more on local bands performing than spinning records in its two-year run.

On CJAY TV’s 25th anniversary in 1985, a Teen Dance Party reunion brought many of the regulars back together. Hosted by Burns, the atmosphere was euphoric. “We had a blast,” enthuses Marta Jack. “Skelly was there and Sandra, Alana and I. It was a wonderful evening. It was really good for Bob. I was so happy for him.” Following a lengthy career in radio, Bob Burns died on October 25, 2010.

Memories of Teen Dance Party remain vivid for Winnipeggers of a certain age who recall the innocent fun the show offered both to participants and viewers. “It was a very simple time,” Marta Jack concludes. “Nothing complicated. We just went to school, danced and hung out. And we always had fun. We used to dance for two hours straight on the show and not think twice about it. Then we’d go to a community club and dance all evening. Everyone loved to dance in those days.”

“It was an awesome experience,” muses Sharon Benjaminson. “Just good clean fun. I wish kids today had those kinds of experiences.”

-

Festival Express

Boomer Magazine

Article by John EinarsonOn Tuesday, June 30, 1970 the infamous Festival Express train pulled into Union Station (now Via Rail) on Main Street south. The 14-coach private CNR train was a sort of rolling thunder revue crossing Canada with stops for concerts at several key cities. Onboard was the cream of the rock ‘n’ roll scene at that point including Janis Joplin, The Band, Grateful Dead, Delaney & Bonnie, Mountain, Ian & Sylvia’s Great Speckled Bird and more. As Grateful Dead drummer Mickey Hart later explained, “Woodstock was a treat for the audience but the train was a treat for the performers.” Indeed, it was.

Dubbed the Million Dollar Bash, the tour was the brainchild of promoter Ken Walker and partner Thor Eaton of the wealthy department store family. Costs were pegged at roughly $500,000 with tickets priced around $10. In the end, the tour lost big money, partly due to poor attendance at the Winnipeg concert as well as cost overruns keeping the performers well lubricated on the journey (the train had to make 2 unscheduled stops on the trip to restock the bar).

“One lounge car was for blues and rock and the other was country and folk,” recalls Sylvia Tyson. “There were jam sessions nonstop. The Grateful Dead ran out of other substances around Winnipeg and started drinking and it was not a pretty sight,” she laughs. According to Ian Tyson’s recollections, “I recall getting into a drinking contest with Janis Joplin and I was seriously outmatched. She drank me under the table. I remember me and Jerry Garcia crawling onto the roof of one of these train cars and howling like coyotes.”

Initially conceived with concerts held in Montreal, Toronto, Winnipeg, Calgary and concluding in Vancouver, the opening and closing dates were ultimately scuttled due to scheduling problems. Some 37,000 attended the inaugural Toronto event, expanded to 2 days with buses chartered to bring in Montreal ticket-holders, buoying hopes for a financially successful tour. However protests outside the CNE Grandstand by a group calling itself The May 4th Movement (after the Kent State massacre) disrupted festivities forcing an increased police presence and reports of violence. The protesters urged those who could not afford the high prices to storm the gates outside the concert to try to get in for free. Fears of similar violence kept many from attending in Winnipeg as protesters outside the Manisphere (Red River Exhibition) site decried the excessive ticket price. Only 4600 tickets were sold here (20,000 tickets needed to be sold for our show to break even).

“It was ridiculous because it was a cheap ticket price for the top acts in music at that point,” states Sylvia. “The presenters in each city were terrified there was going to be some kind of riot from this May 4th Movement. That had such an adverse affect on the whole thing. The mayor of Calgary got in on the act declaring, ‘Let the children of Calgary in for free’ and Ken Walker said ‘Screw you’ and punching him. Then the manager of the stadium said, ‘I have a solution. We’ll let them in for free but they have to pay to get out!’”

Nonetheless, the Winnipeg stopover proved memorable for performers and attendees. Having spent two days partying non-stop on the two lounge cars commandeered for jam sessions, several performers went in search of some local colour. The Grateful Dead and their crew headed to the Pan Am Pool on Grant Avenue where Jerry Garcia organized a relay race between various stoned musicians.

Delaney and Bonnie Bramlett chose to disembark and take a room at the downtown Sheraton Carlton Hotel. Front desk man Brian Levin and fellow Expedition To Earth bandmate Dan Norton took the two performers on a tour of the city. “We spent the day driving around showing them highlights of our Winnipeg,” recalls Dan. “We stopped at the A&W Drive Inn on Portage Avenue across from Polo Park and confused the patrons as we got out and walked around, had our burgers and fries and continued on back to the train to check out what was doing. One of the reasons they were at the Sheraton was Bonnie wanted to protect Delaney from Janis Joplin. Delaney and Bonnie were two of the nicest, most down to earth people that you could ever hope to meet. No pretensions.”

Joplin herself determined to take in the sights. “A few of us got a cab and said, ‘Take us to where the freaks are,’” she told Winnipeg Free Press reporter Ken Ingle. “We went to this park and there was an entire beautiful crew of people just lying around and playin’ the guitar.” The carefree ambiance surprised the hard-living singer. “There’s hippies in the fountain and nobody’s bustin’ them. I mean, if you walked into a fountain in New York City, you’d be in jail in five minutes. But there’s forty hippies floundering around in the fountain and standing under the spray.” Festooned in feathers, scarves, garish costume jewelry, and pink sunglasses, Joplin waded into the warm waters under the watchful gaze of the Golden Boy. Few hippies took notice of her.

That same casual air was also present on the train. “There was no security, no bodyguards, nothing,” recalls Jerry Dykman. “I just walked through the coaches. Nobody stopped me. I was able to chat with everyone. Janis Joplin was there drunk as a skunk, a bottle of tequila in her hand. It was all peace and love.” Local music journalist Andy Mellen also boarded the train and encountered the queen of the hippies. “I sat down with Janis in this empty coach and she poured me a finger of Southern Comfort. I had my tour program with me and I asked Janis to sign the photo of her in it,” he recalls. “She signed it ‘Love, non-professionally, Janis Joplin’. I have that framed on my wall. I was this 20 year old kid and here was this legend. She was so courteous to me.” Three months later Joplin would be dead.

Another visitor to the train was Randy Bachman, recently departed from the Guess Who. “I was sitting there with Jerry Garcia and other members of the Grateful Dead, Janis Joplin, Delaney & Bonnie and their band, guys from The Band, Leslie West from Mountain. Players would wander in and out, pull up a chair, plug into one of the little amps they had and just pick up on the flow of the ongoing blues jams.” An abstainer, Randy had to deal with the various substances passed around. “I sat by an open window because the smoke was so thick. As the joints were passed around someone would nudge me and offer one. ‘No thanks’ and it would get passed along to the next player. I just wanted to play with anybody.”

The following afternoon, Canada Day, the performers decamped for the Stadium concert. Ticket-holders began queuing up hours before the 11:00 gate opening then made a dash for a prime spot of the turf to spread out blankets. The concert commenced at 1:00 with local acts Walrus (featuring Joey Gregorash) and Justin Tyme before the headliners took to the stage beginning with Montreal’s Mashmakhan who were enjoying hit status with “As The Years Go By”. Folksingers Tom Rush and Eric Andersen had a tough time soothing the crowd looking to rock. Bluegrass trio James & the Good Brothers had not been together long but managed to earn applause. James was ex-Winnipegger Jim Ackroyd formerly of The Galaxies. Quebecois singer Robert Charlebois tried vainly to stir up the crowd but his set of mainly francophone songs went unappreciated.

Blues guitarist Buddy Guy brought the audience to their feet for a rousing set that included wading into the audience playing his guitar. An enormous roadie in a jumpsuit followed behind letting out what must have been a 100 ft cord. Ian & Sylvia were backed by their recently formed country rock band The Great Speckled Bird featuring guitar virtuosos Amos Garret and Buddy Cage. Throughout their set, Jerry Garcia stood right onstage oblivious to the audience to watch Buddy play his steel guitar. “In Winnipeg some drug-crazed hippie climbed up on the stage and tried to grab N.D. Smart’s drum sticks,” laughs Sylvia. “Big mistake. N.D. put down his sticks, punched him, and went back to playing without missing a beat. By the time we turned around it was all over.”

Mountain, led by massive guitarist Leslie West playing a tiny Gibson Les Paul junior guitar, blew the audience away with their powerhouse sound (and earned an ovation introducing Canadian drummer Corky Laing), ending with “Mississippi Queen”. Between changeovers, Randy Bachman wandered out onstage unannounced armed with an acoustic guitar. “I was so nervous that I ended up spelling ‘American Woman’ wrong,” he recalls.” I was doing the ‘I say A, M, E’ intro and I missed a letter. I was going to do a whole mini set but I got so flustered I walked off halfway through. People thought I must be stoned but I was just out of my element.” He later returned to jam with Delaney & Bonnie whose raucous R ‘n’ B set was punctuated by the singing of Happy Birthday to Delaney.

Some of The Grateful Dead were not in a friendly mood and at one point uttered a profanity-laced invective aimed at an audience member. But as Chris Doole recalls, “When the Dead performed ‘Alligator’ it got into this groove where it started to sound like 25 perfectly synchronized locomotives with Garcia’s tasty little trills on top of it all. Everyone's attention was just nailed to it.”

It was past midnight by the time The Band and Joplin each mounted the stage and some concert goers had already left. Looking like rustic mountain men, The Band played an exceptional set drawing from their first two albums along with a few old chestnuts including Little Richard’s “Slippin’ & Slidin’”. Garth Hudson’s elongated organ intro to “Chest Fever” drew on several old hymns and was mesmerizing. Backed by The Full Tilt Boogie Band (consisting of mostly Canadians), Joplin rocked hard and won over the weary crowd. “I remember she said, ‘You guys certainly know how to throw a ... train’” recalls Chris Doole.

A brazen young man managed to amble onstage near the end of her set. “How about a kiss for the boys from Manitoba?” he queried. Smiling, Joplin consented. As he turned to leave, the young man thanked the stagehands. “Why are you thanking them, honey?” sassed Joplin, “They didn’t do nothing for you!”

“Everyone on that train was at their peak,” notes Sylvia Tyson. “The Band was at their best and Janis, too. She was just coming into her own as the singer she really was just before she died.”

The following morning, after another night of partying and jamming, the train slowly pulled out of Union Station bound for Calgary and the final concert. “I knew a girl who was at the Winnipeg concert,” remembers Hilary Chase, “who ran up to the stage at some point, was noticed by guys in Janis Joplin’s band and ended up travelling to Calgary with them on the train.”

“It's amazing,” concludes one local observer ruefully, “that anyone can remember anything about that event by the amount of drugs and alcohol that was digested both by fans and performers.”

-

The Beatles on Ed Sullivan

Lifestyles 55 Magazine

Article by John EinarsonFor the baby boom generation, it’s a defining moment: the night The Beatles made their live North American television debut on The Ed Sullivan Show February 9, 1964. Several million Canadians, including yours truly, tuned in that evening and had their world changed forever. One observer noted it was as if our world suddenly turned from black and white to Technicolor. Overnight everything became Beatles, Beatles, Beatles.

“I will never forget that night,” states Colleen Titanich. “My father thought it was the beginning of the end of the world because they had long hair. I was eight years old and I thought they were so cool!” Recalls Marnie Hocken, “I could not wait for The Ed Sullivan Show. I sat right in front of the television, couldn’t get close enough. I cried when they were singing and my father laughed at me and said they would only last a few months. The performance was over way too fast but I was completely hooked.”

At school the next day there was only one topic of conversation. While the girls gathered to affirm their love for their favourite Beatle, the boys plotted forming bands. Within weeks the number of bands in the city doubled. “I had been thinking about learning to play guitar for about a year prior to that date but February 9, 1964 cinched my decision,” states Paul Newsome. He wasn’t alone.

“I remember watching it at home in our basement sitting around our 17-inch black and white television,” recalls local radio personality Tom Milroy. “Virtually everyone with a TV was watching Ed Sullivan that night. When I first heard ‘All my Loving’...Wow! I soon dumped the accordion and took up the drums.”

“With my family gathered around the TV my father’s first comment was ‘How can you listen to that noise!’,” Gerry Gacek remembers. “Soon thereafter I made the major investment of buying an EKO violin shaped bass guitar because it looked like Paul McCartney’s bass. I took the bus all over Winnipeg with my buddies looking for stores that carried Beatle boots. There was an ever-present battle with my parents to grow long hair without them noticing and then not get sent home from school.”

For Burton Cummings, the inaugural Beatles appearance had repercussions at school. “That Monday morning after the Beatles’ North American debut, A.J. Ryckman, the principal of St. John’s High, called me down to his office. I was trying to grow my hair at the time to look like The Beatles’ style. Ryckman kicked me out of school for hair that barely came down over my ears and told me not to come back until my hair was ‘cut properly’. I didn't get a haircut for a whole week.”

As John Tataryn remembers, “My best friend had a sister and after the Ed Sullivan appearance his house was filled with junior high girls playing Beatles 45s and screaming. They bought Beatle wigs and plastic Beatle guitars.”

Children’s entertainer Al Simmons witnessed the excitement that night. “As soon as the girls in the audience started screaming, I was transfixed. There was a gigantic shift in culture literally overnight and it was amazing to witness it. My Dad bought my brother and I Beatle wigs which were basically a fun-fur bag with an elastic edge that looked like furry bathing caps.”

The Beatles appearance was a life-changer for singer/songwriter/record producer Dan Donahue. “I had a sense that watching them on that very first Sullivan appearance that history was being made. The Beatles pretty much served to chart my life’s course.”

“Sundays meant going to Grandma’s for roast beef and TV, which we didn’t have ourselves, starting with Ed Sullivan, then Bonanza and maybe Candid Camera,” recalls former NDP cabinet minister Gord Mackintosh. “Cousins were there and part way through the Beatles’ performance I realized for the first time there was a generation gap in the family. The adults were all saying ‘Isn’t that silly’. We were all saying ‘Isn’t that sensational!’.”

-

Métis Fiddlers

LifeStyles 55 Magazine

Article by John EinarsonThe fiddle is at the centre of traditional Métis culture in Western Canada, heard at weddings, New Year’s celebrations and other social gatherings where dancing, including the Red River Jig, go hand-in-hand with fiddle music. Not to be confused with the classical violin, fiddling is a distinctly Canadian approach to bowing the strings. Fiddlers were generally self-taught with fiddle songs drawn from Acadian music (from French settlements along the Atlantic coast) and Scottish jigs and reels passed down from generation to generation by ear. Often hand-made fiddles were used.

“Fiddling is extremely important to Manitoba culture in that we have such long running fiddle and dance traditions,” notes renowned local fiddle champion Patti Kusturok, known as “Canada's old-time fiddling sweetheart.” A member of the North American Fiddlers Hall of Fame, Patti is a six-time Manitoba Champion, three-time Grand North American Champion. “Here on the prairies, fiddling and old time square dancing go hand in hand,” she notes, “and the style of the music is always played with dancing in mind. It all started with the house parties, usually in the kitchen, and the music was accompanied by just the feet.

Two of the best-known Métis fiddlers from Manitoba were Andy Dejarlis and Reg Bouvette. Together they account for close to 100 fiddling albums and toured across Canada. Accompanied by the Red River Mates, Andy Dejarlis began performing on radio in Winnipeg in 1937, graduating to television in the 1950s. After stints in Vancouver and Montreal, he returned to Winnipeg where he continued to play festivals and dances. In his lifetime, Andy published over 200 fiddling songs under his name. After an appearance on CBC TV’s Don Messer’s Jubilee, Messer, no slouch on the fiddle himself, is said to have declared Andy Dejarlis the greatest exponent of old-time fiddling in Canada.

Reg Bouvette cut a dashing figure with his distinctive blue fiddle. Little is known about his early years but there is no doubting his influence on young fiddlers. “I first met Reg Bouvette in 1977 at the Garden City Mall fiddling contest,” Patti remembers. “I was just a kid. My mom put me on her shoulders so I could see and I was hooked. I spent hours listening to his records. To me he was huge star.” In 1986, Patti recorded an album of fiddling numbers with Reg Bouvette entitled The King and the Princess on Sunshine Records. “Of course, it goes without saying that it was a huge honour for me,” she smiles.

Hailing from Selkirk, Manitoba, fiddler Mel Bedard was the first to use the term “Métis” on a record sleeve. A close friend to Andy Dejarlis, Bedard mentored young Patti who also cites Métis fiddler Marcel Meilleur who played second fiddle or harmony on all of Andy Dejarlis’s recordings and at live shows. Raised in the tiny rural community of Vogar, Manitoba, Cliff Maytwayashing is another talented fiddler in the Métis tradition. “If you didn’t tap your foot to his playing, you’d better check your pulse,” laughs Patti.

Winnipeg-born fiddler Wally Diduck cut a wide swath through the music world in his lengthy career, not only appearing on local television productions like Red River Jamboree, Sesame Street (portions of the Canadian content were produced out of Winnipeg) and My Kind of Country starring Ray St. Germain. Unlike many of his self-taught contemporaries, Wally was a graduate of the Royal Conservatory School of Music at the University of Toronto. Besides playing alongside the likes of Rod Stewart, Anne Murray, Buck Owens and Kenny Rogers, Diduck also performed at Rainbow Stage and the Manitoba Theatre Center in productions of Fiddler on the Roof, The Sound of Music, West Side Story and Chicago. His colourful fiddling can be heard on singer, songwriter Ray St. Germain’s signature song “The Métis”.

One of our province’s top fiddlers, Stan Winistock from Portage La Prairie, added fiddle to the 1973 Guess Who hit single “Orly”. Fiddlers like Oliver Boulette from Manigotogan, Tayler Fleming from Minitonas, and Portage La Prairie’s Melissa St. Goddard are carrying on the Métis fiddling tradition.

-

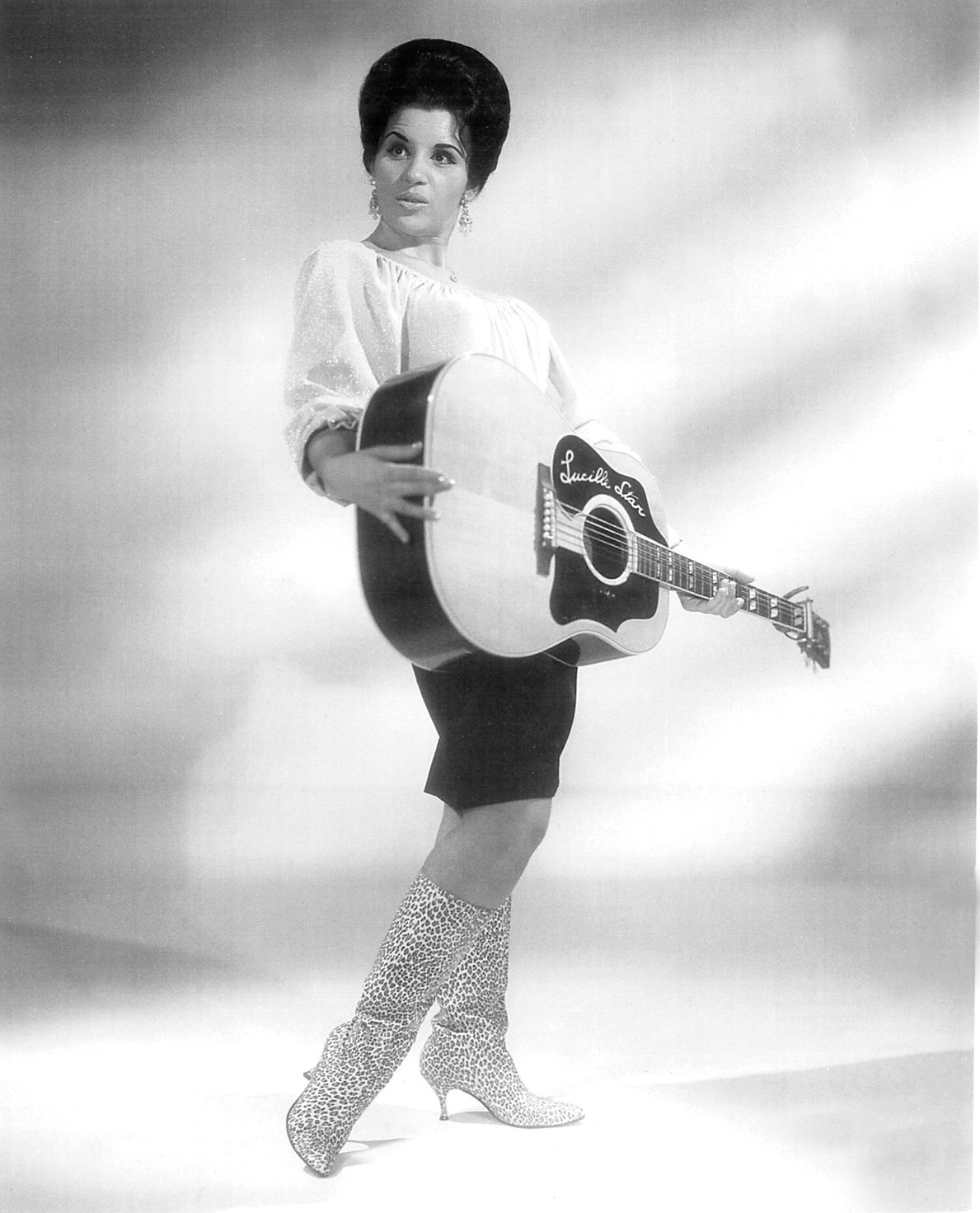

Lucille Starr

Lifestyles 55 Magazine

Article by John Einarson“Quand le soleil dit bonjours aux montagnes”. Whether you speak French or not, the opening line to Lucille Starr’s million-selling 1964 hit “The French Song” is instantly recognizable. Produced in Los Angeles by Herb Alpert (of Tijuana Brass fame), the single became the first million-selling record by a Canadian female country music recording artist and topped record charts worldwide. At one time, Lucille held the top five spots on the South African charts and in the Netherlands “The French Song” was #1 for nineteen weeks straight. Lucille’s name remains forever associated with that sentimental bilingual ballad.

Lucille Starr passed away at her home in Las Vegas on September 4, 2020. She was 82.

Born Lucille Marie Raymonde Savoie in St. Boniface in 1938, Lucille lived on Langevin Street for her first seven years. “Some of the sweetest memories come from my childhood in Winnipeg,” she reminisced from her home in Las Vegas a few years back. She grew up in a musical family. “My daddy would play the fiddle and my mother sang.” Lucille began singing in church in St. Boniface.

The family moved to Mallairdville, British Columbia where Lucille would launch her singing career in her teens teaming up with guitarist/singer Bob Regan (Bob Frederickson) as rockabilly duo Bob and Lucille before renaming themselves The Canadian Sweethearts. The Sweethearts enjoyed several hits in Canada and the United States. Signed to A&M Records, record producer Herb Alpert brought Lucille into the recording studio to record a solo record, “The French Song”.

“Actually, it was re-named that,” Lucille explains, “because Herb couldn’t pronounce the original French title. He would say, ‘I don’t care if I can’t understand the word, I know this is a hit’.” Alpert contributed the trumpet intro to the record. Released in the spring of 1964 at the height of Beatlemania, “The French Song” captured hearts all over the world. The following year Lucille was fêted with an invitation to be Grande Vedette (top star) of Amsterdam’s Grand Gala du Disques, an international music cavalcade. She was in illustrious company following on the heels of previous honourees Frank Sinatra, Barbra Streisand and Charles Aznavour. “I was the first Canadian or American to do a television special in the Netherlands,” she states with pride. Lucille’s popularity extended to Belgium, Switzerland, Mexico, Guam, the Philippines, Japan, and Korea. She performed in many of these countries, and in South Africa the Prime Minister held a special luncheon in Lucille’s honour at their parliament. She headlined a five-week tour in South Africa in 1967 where she received several gold records.

Her marriage was fraught with turmoil from the get-go and with Lucille’s solo success, Regan became more abusive. “When I started getting hits, he became very jealous,” recalls Lucille. “Bob wanted me to fail.” Their turbulent relationship was portrayed in the Canadian stage production Back To You: The Life & Career of Lucille Starr by Tracy Powers which was staged at the Prairie Theatre Exchange in 2010.

Lucille scored further hits with “Colinda”, “Jolie Jacqueline”, and a bilingual cover of Ray Price’s “Crazy Arms”. Her yodeling abilities were put to good use on the popular television show The Beverly Hillbillies where she provided the singing voice for Cousin Pearl. Lucille recorded in Nashville with noted producer Billy Sherrill, the man behind hits by Tammy Wynette, Charlie Rich, and George Jones. The partnership yielded two albums and the hits “Too Far Gone”, “(Bonjour Tristesse) Hello Sadness” and “Send Me No Roses”.

A fascinating sidebar to Lucille’s story is that the former Prime Minister of Croatia Kolinda Grabar-Kitarovic’s mother liked Lucille’s “Colinda” so much that she named her daughter after the song.

In the 1980s she married Bob Cunningham, a Sarnia, Ontario businessman, and appeared regularly in Las Vegas where the two resided. Lucille continued to tour worldwide releasing Lucille’s Starr’s Greatest Hits in Europe in 1982, and picking up another gold record. In 1996 she was added to the Nashville Walk of Stars in the Country Music Hall of Fame. The Canadian Country Music Hall of Fame inducted Lucille in 1989.

Reflecting on her long career, Lucille stated, “When I was just a kid all I ever thought about was getting up on a stage and singing. I never thought about stardom or gold records. It’s like the happy ending you read about in story books.”

-

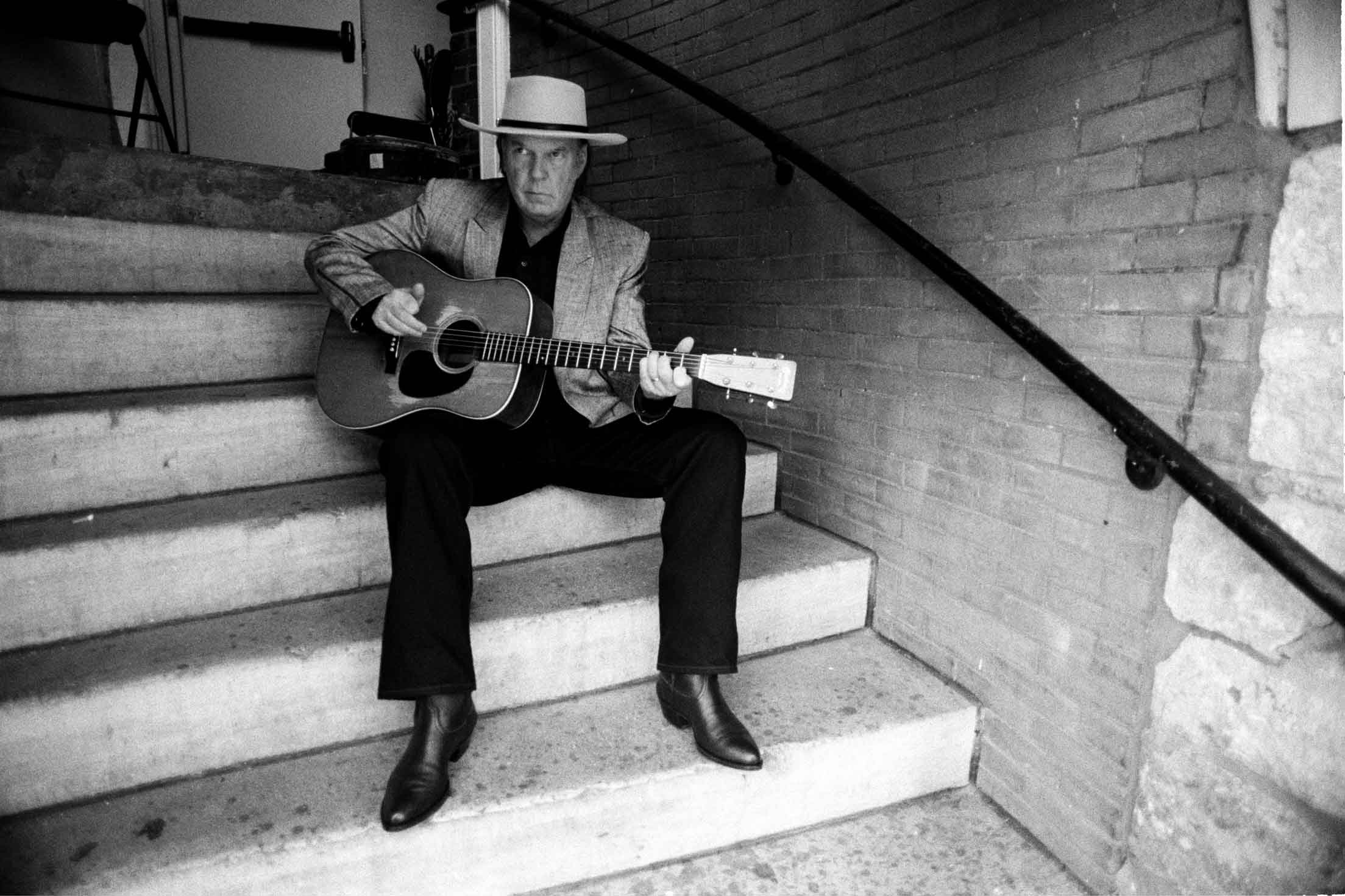

Neil Young

Lifestyles 55 Magazine

Article by John EinarsonFifty-nine years ago this month, internationally-renowned rock music iconoclast Neil Young made his first ever recordings at CKRC radio’s tiny recording studio in the old Winnipeg Free Press building on Carlton Street in downtown Winnipeg. On the afternoon of Tuesday, July 23, 1963, local rock ‘n’ roll quartet The Squires – Kelvin High School student Neil Young on lead guitar, Grant Park High students Alan Bates on rhythm guitar and drummer Ken Smyth, along with bass player Ken Koblun from Churchill High School – recorded a couple of original compositions from Young under the direction of recording engineer and CKRC deejay Harry Taylor. Fellow CKRC deejay Bob Bradburn is listed as record producer but it was Taylor who was calling the shots. Bradburn’s contribution was hitting a large gong with a mallet at intervals in one of the songs.

“The big thing was to get a DJ behind you,” recalled Neil of his embryonic years on the local community club circuit. “Bob Bradburn was our connection at CKRC.” Although Bob’s on-air slot was the mid-morning show, nine to noon when teens were supposed to be in school, he was, nonetheless, a name around the city. Bob adopted the band, plugging their engagements on the radio and hosting their community club dances. On July 12, 1963, he arranged an audition for The Squires with CKRC recording engineer Harry Taylor. Having suitably impressed Taylor with fifteen or twenty of their best instrumentals, Harry invited them back a week later for a run through of two of Neil's compositions, The Sultan and Aurora. Satisfied with these two songs, Taylor arranged a recording date for July 23. On that day, Neil Young made his recording debut. Two months later a 45rpm single, The Sultan, backed by Aurora, was released locally on local V Records label, quite a feat for such a young band. Owned and operated by Alex Groshak out of his home in Windsor Park, V-Records specialized in Ukrainian music, the label’s biggest success being popular duo Mickey & Bunny. But Groshak took a chance with The Squires. Some 300 copies of the single were pressed. It received airplay on CKRC.

Both sides of the single were guitar instrumentals in The Ventures and British instrumentalists The Shadows style. The recordings reveal Neil’s progress on guitar, though nothing of the nimble fingers he would show on later recordings. “With The Sultan,” Neil reflected to me, “it was good to have it out but I hadn’t got the sound I was after yet. It was my first recording session and I was just glad to be there for the experience. I was still searching for that right sound.”

That search brought Neil Young’s Squires back to CKRC’s 2-track studio on April 2, 1964 with Harry Taylor again at the controls. With The British Invasion in full swing spearheaded by The Beatles and their Merseybeat contemporaries, this recording session featured the debut of Young’s vocals. “I think we recorded a song called Ain’t It the Truth written by me,” says Neil. “There were tapes of those songs around but they are probably lost now. We did about twenty songs.” Decades later two songs from that April 1964 session surfaced: I Wonder featuring Young on double-tracked vocals and an instrumental track, Mustang. At the completion of the session, Neil asked Harry Taylor what he thought. Neither ever forgot the reply: “You’re a good guitar player, kid, but you’ll never make it as a singer.” Recalls Young, “People told me I couldn’t sing but I just kept at it.” The recording wasn’t released at the time.

Young would take a second stab at I Wonder in Fort William (Thunder Bay) at radio station CJLX in November 1964 while still based in Winnipeg. At that same session, the band recorded Young’s I’ll Love You Forever, a love song to his Winnipeg girlfriend Pam Smith that featured dubbed in ocean sounds. In March, 1965, Young and The Squires recorded his composition I’m A Man And I Can’t Cry at Mickey & Bunny leader Mickey Sheppard’s basement studio in West Kildonan. A month later, Neil would take The Squires, now down to himself, Ken Koblun and drummer Bob Clark, to Fort William for several months before trying his luck unsuccessfully in Toronto. Heading south in March 1966 he would run into Stephen Stills and Richie Furay in a Sunset Boulevard traffic jam. Together they would form the Buffalo Springfield. Neil Young had found the fame he had been searching for.

In June 2009, Neil Young released the first volume of his highly-anticipated 10 disk Neil Young Archives box set retrospective pulling together some of his best-known recordings from 1963 to 1972 along with dozens of unreleased tracks. Among those unreleased tracks were the recordings made by The Squires between 1963 to 1965. “Winnipeg was where it all happened for me,” he stated.

Podcasts

Let it Roll podcasts with Nate Wilcox

Host Nate Wilcox asks John Einarson dabout the ups and downs and self-imposed limitations that kept Arthur Lee and Love strictly a Southern California phenomenon. Listen Now!

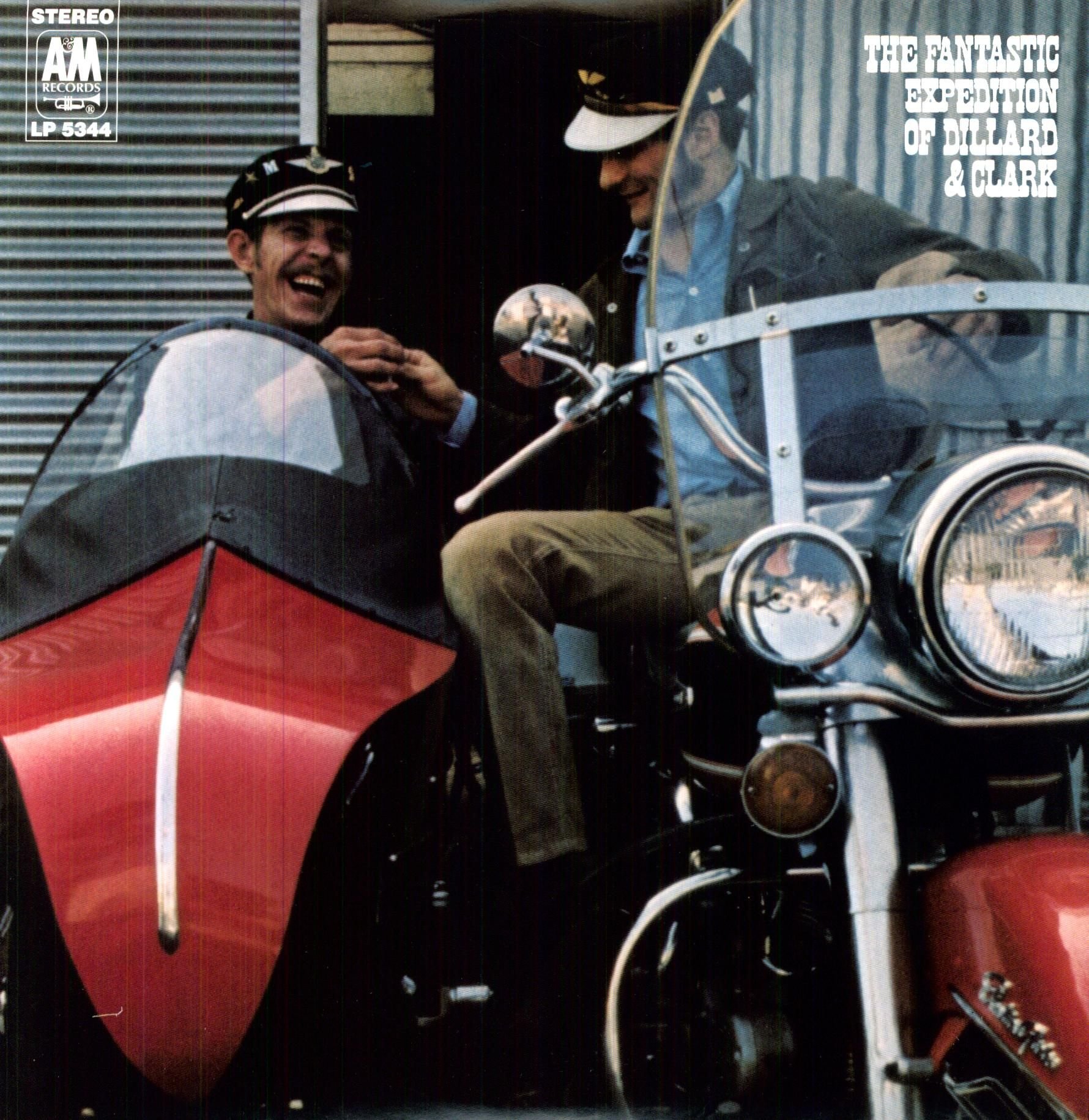

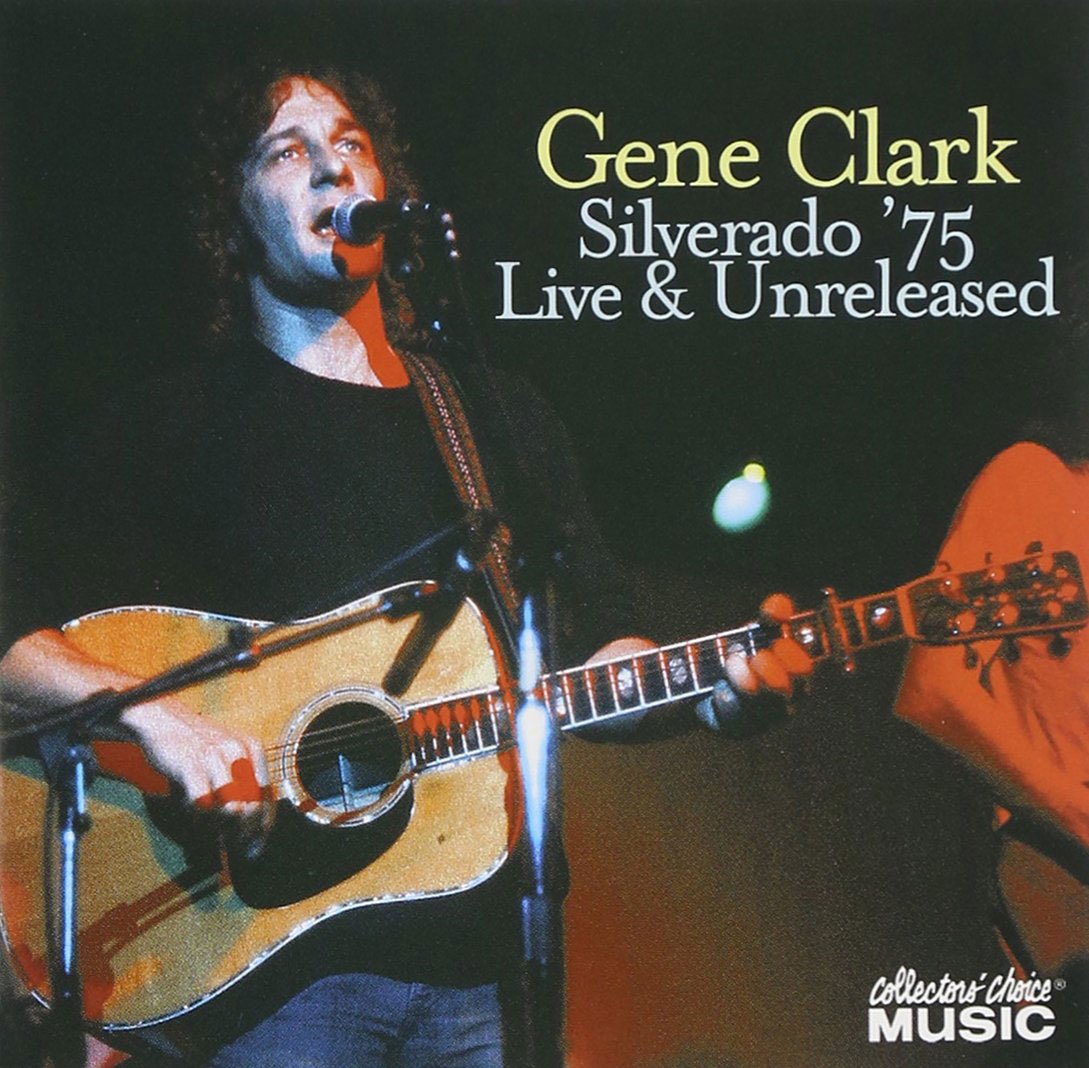

Host Nate Wilcox and John Einarson discuss the career of Gene Clark, both with the Byrds and his later solo efforts and with Dillard & Clark. Listen Now!

This ‘Let it Roll’ podcast has John talking to Nate Wilcox about Neil Young, Stephen Stills, Richie Furay and the music of Buffalo Springfield. Listen Now!

Dusty Discs Radio podcasts

Join John Einarson as he discusses Canadian music on Dusty Discs Radio podcast “Liner Notes: Revealing Chats with Canada’s Retro Music Makers”. Listen Now!

Liner Notes

Liner notes accompany records, CDs and digital releases. They are an important element in the presentation of music. Einarson has contributed his comments to many liner notes. Check them out, you’ll find some great stories here.

-

Gene Clark & Carla Olson

So Rebellious A Lover

Extended Liner Notes by John EinarsonGene Clark’s career had pretty much hit rock bottom by the early 1980s. The former Byrds founder and singer/songwriter, the one out front with the tambourine, left the group in early 1966. Anointed America’s Beatles, a tag the Byrds found near impossible to live up to, the five band mates were never the best of friends. A country boy of simple virtues, Gene was way out of his depth in the fast hustle of the Hollywood music milieu. A combination of reluctance to fly, sniping from his fellow Byrds over his hefty royalty cheques (Gene was the band’s principal songwriter) and ill at ease with the god-like adulation bestowed on the band members, forced Clark to fly the coop.

Despite consistently releasing critically acclaimed and creatively brilliant albums beginning in 1967 and sporadically thereafter, commercially Gene’s records had largely fallen on deaf ears. At times his frustration at failing to achieve a commercial breakthrough was palpable and nearly erupted into fisticuffs with music mogul David Geffen who financed Gene’s magnum opus, 1974’s No Other, only to leave it twisting in the wind without promotion. It was clear in the music business that Gene Clark was persona non grata, too much of a loose cannon to risk signing. His alcohol and drug use only heightened the unease surrounding him.

By the early 1980s, Gene had been dividing his time between touring with fellow ex-Byrds drummer Michael Clarke in a sort of Rolling Thunder Revue of buddies dubbed The Byrds 20th Anniversary Tribute show and recording with a few close friends. To say the Byrds tribute shows, which included at times members of The Band, Beach Boys and Firefall, were ramshackled would be polite. Coked and boozed up, Gene and his band of merrymakers stumbled through a set of Byrds favourites each night.

In sharp contrast, writing and recording with friends Pat Robinson and onetime Byrd John York at Silvery Moon studios in Laurel Canyon proved to be much more satisfying. As CRY (Clark, Robinson and York, later expanded to CHRY with the addition of pianist Nicky Hopkins), the sessions offered an oasis for Gene and a creative outlet, although his bad habits remained. Unfortunately, there was no commercial interest in CRY and the recordings would languish for several years before seeing the light of day after Gene’s death.

Besides the Byrds tribute debacle, Gene had been touring with his own band under the name FireByrd with a handful of younger players plus buddy Michael Clarke. But by the fall of 1984, FireByrd was running out of tinder.

Clearly Gene needed a lifeline. At what would become FireByrd’s swansong gig at Madame Wong’s West, a club on Wilshire Boulevard in West Los Angeles, Gene would meet singer/songwriter Carla Olson and her manager Saul Davis.

“Saul and I intentionally went to see Gene that night actually because we had never met him,” explains Austin, Texas-born Carla, who had fronted the Textones. Near the end of FireByrd’s set that night, Gene’s compadre Tom Slocum invited Carla to join Gene onstage. “I didn’t know Tom, but he introduced himself. He said, ‘You should get up and sing with Gene on the encore.’ I replied, ‘That’s okay, Tom. I’m just here to enjoy the show.’” Slocum persisted. “‘They’re going to do ‘Feel a Whole Lot Better.’ When they started to do the encore, he literally grabbed me by the hand and pulled me up on the stage and threw a tambourine at me and said, ‘Sing!’ In the middle of the guitar solo, Gene leaned over and said, ‘Hi, I’m Gene Clark.’ There’s a photo, actually, of that moment, the moment we first met. Then after the show we went backstage and talked with him.”

Carla’s Textones were among a brand-new breed of punkish country-rockers. The early ’80s Paisley Underground revival of 1960s power-pop in Los Angeles had spurred a healthy country-rock/Americana roots scene. This would ultimately spawn the alt.country movement, spearheaded in the late ’80s and early ’90s by such artists as Lucinda Williams, Gillian Welch, Victoria Williams, the Jayhawks, and Son Volt, among others. These performers took as their guiding inspiration the works of doomed country-rock pioneers like Gram Parsons, the Flying Burrito Brothers, the Sweetheart of the Rodeo-era Byrds, and Dillard & Clark.

Carla came out to Los Angeles in 1978 with friend Kathy Valentine and formed the Textones the following year (Kathy later took a spot in the Go-Go’s). Carla’s big break came when she appeared alongside Bob Dylan in the video for “Sweetheart like You” from his acclaimed Infidels album. She would later team up with Rolling Stones guitar great Mick Taylor as well as ex-Manfred Mann singer Paul Jones among others.

“I was aware of who Gene was, certainly with McGuinn, Clark & Hillman,” Carla continues. “He was always kind of the serious guy in the Byrds. He wrote the most beautiful melodies, the most haunting.”

The arrival of Carla and Saul at that particular point in Gene’s life and career, while certainly serendipitous, would prove fortuitous. It gave Gene the chance to return to a more roots-based, acoustic singer-songwriter format—always his strength—and offered fresh, new associations that would recharge his creative batteries.

“Gene had so thoroughly destroyed his name in the music industry by the time that we first met him that it was really difficult to get any opportunities for him,” laments Saul Davis, who would take on managing Gene.

“We got together quite often at Gene’s house for business,” Carla recalls, “and I would hang around while Gene and Saul did business or we were waiting around for Gene to make one of these huge dinners. He used to love to make these big meals. Gene would start to play guitar and other people would come over like Tommy Slocum and we’d all be playing guitars and singing. I can’t remember who came up with the idea of recording this stuff. I have never really felt comfortable with my voice and I felt so honored that Gene allowed me to sing with him. He was just so totally giving that way. He never looked down his nose at anybody that was singing. He never put anybody down.”

Two songs ultimately destined for the album emerged out of those impromptu kitchen sessions. “One time I remember we were sitting there,” Carla recalls, “Gene and me and Saul, Michael Clarke, and somebody else, and we got on this ‘Hot Burrito’ kick. Gene just started playing it on acoustic guitar. I just was singing harmony under my breath. He played something else, too, then he said, ‘I’ve got this great song that my brother wrote. Listen to this.’ I thought it was a Woody Guthrie song from the 1930s. I just fell in love with it. He and Rick wrote it together.” The song was “Del Gato,” one of the highlights of the album, a poignant tale of early California history. “When we were living in Mendocino with Gene,” Rick explains, “we didn’t have a TV. That’s how we ended up writing ‘Del Gato’ because I was reading about the early history of California. That’s how the idea for ‘Del Gato’ came about and we wrote it in one evening.”

After a few trial runs singing with Gene and sharing songs plus recording with member so the Textones as well as The Long Ryders, in early 1986 Gene and Carla began sessions for their duet album, So Rebellious a Lover (the title taken from the lyrics to “Del Gato”) at Control Center studios in Los Angeles with drummer Michael Huey producing. Michael had previous drummed for Glenn Frey, Juice Newton, Joe Walsh, and Chris Hillman when Saul approached him with the offer to produce Gene and Carla. “I came of age in the 1960s with the Byrds,” states Michael. “Never in my wildest dreams did I ever imagine I would be in a recording studio producing Gene Clark. He was one of the fathers of modern rock ’n’ roll. And lo and behold he’s out in the studio with Chris Hillman! That pretty much blew me away, personally. The engineer and I just kept looking at each other all day long going, ‘I can’t believe it!’ It was pretty amazing to have these two guys there. Gene was such a wonderful man, too. Never aloof or arrogant, a pretty down-home kind of guy. He had the aura about him, but he never played on it. He was just a very charismatic guy in a kind of quiet way.

“Actually, it was the four of us—Gene, Carla, Saul, and myself—who steered that album through,” insists Michael. “We ploughed through a lot of material before we picked those eleven songs. We knew that the album was going to be rather dark because that tended to be Gene’s style. There were some uptempo, happier, rockier songs but they just didn’t seem to fit on that album. He really, really loved those down songs. That’s what he listened to, that’s what he wrote, and that’s what he played. Great songs, but any time we had something uptempo, he didn’t like it. He just didn’t like fast songs or to rock that much. That’s truly the way he was. So, we knew it was going to be kind of a dark and introspective album and we decided to go with it because it seemed to fit. That style wasn’t so much Carla. That was more Gene, as far as the direction, more of a Gene vibe, although Carla had a lot of input.”

Using a stripped-down, back-to-basics approach and framing the songs in a rootsy folk/country context, Michael managed to create the perfect setting for Gene and Carla’s songs. While Gene dominates the material, Carla holds her own, contributing such standout compositions as “The Drifter” and “Are We Still Making Love.”

For the sessions, Michael assembled a solid backing band whose talents complemented Gene and Carla’s musical vision. “We had pretty much an all-star rhythm section,” he states. “In Los Angeles musicians’ circles they were quite well known. We had Otha Young on acoustic guitar from Juice Newton’s band, and Skip Edwards did a lot of keyboards on it. He later worked with Dwight Yoakam.” Long Ryders guitarist Stephen McCarthy added dobro and lap steel. Michael provided the drums. Chris Hillman (who appeared on almost every album Gene released throughout his career) guested on mandolin on several tracks, demonstrating once again his long-standing support for Gene.

Despite the stellar supporting players and stressless studio vibe, Gene endured considerable personal discomfort throughout the sessions. As Michael remembers, “He was going through heavy stomach problems and intestinal problems and he was in pain a lot of the time we were recording and had to be taken to the hospital on one occasion. He would double over in pain. He was popping a lot of aspirins and Tylenol and drinking monumental amounts of coffee and smoking. I think that helped to speed up his death because all of that stuff pretty much ate a hole in his stomach. But he wasn’t drinking alcohol. He was on the wagon, or at least he was not drinking around me.”

Carla credits Gene for providing her with a musical education. “Gene taught me so many things about singing,” she recalls, “He used his voice like a woodwind or a cello, with subtlety. Gene showed me that I had to back off the mic — not just belt it out — to make every word count. Because he had played solo so much, I had to find my place in the songs, whether to use a different inversion of a chord, or find a harmony that fit. Many times I opted for a unison part but an octave above. That seemed appropriate to create a single voice on some lines.”

Saul secured a recording contract with UK indie label Demon but finding a US deal was difficult given Gene’s tarnished reputation. “Saul was gently trying to convince Gene that people were not exactly knocking down doors to sign him,” states Carla. “But that was hard because Gene always had his ego.” In the end Saul managed to convince Rhino Records, best known as reissue specialists, to put out the album. So Rebellious a Lover presented Gene and Carla’s exquisite acoustic folk/country-based songs with subtle, unobtrusive backing. “Probably it was a part of Gene that everyone longed to hear,” suggests Carla. “Most people never got to hear that on his records because of all the production. The whole idea of doing that record stripped down was to let the voices be heard. Minimal instrumentation was the direction we wanted.” The album found Carla’s songwriting well matched to Gene’s high standards and her rich, full voiced delivery a worthy partner to his melancholy baritone.